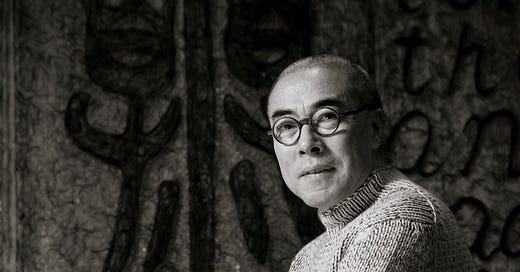

Gu Wenda is a contemporary artist born in China. He currently lives in New York. His paternal grandfather was the first to introduce the spoken word into Chinese theater, in which the lines were always sung. During the Cultural Revolution, Gu’s grandparents were taken away for “reeducation” by the authorities.

Like many young people in China during the 60’s, he aspired to be a Red Guard. His work as a Red Guard was to help streamline the Chinese language. Although his artistic background is in classical ink painting, his first public works were Mao portraits that were mass-printed as posters. However, since the mid-80’s, much of Gu’s work has been conceptual. Traditional methods and themes, such as Tang Dynasty poetry and calligraphy, are juxtaposed with contemporary methods and themes, such as his incorporation of elements of the human body into his works.

In 1986 one of his shows, featuring invented ideograms, was shut down by the authorities—who assumed that since they could not read what was written, the message must be subversive. The fact that they could not be read was undoubtedly subversive in itself.

Gu’s work invites us to consider the relationship between text and culture, as well as what relationship cultures can have with themselves and each other in this period of multiculturalism. Many of his works use invented text, intended to frustrate and/or inspire the viewer. These invented texts serve to remind the view of the limitations of human knowledge despite the seeming omnipresence of that knowledge. And perhaps to help us navigate meaning— and the loss of it—in our increasingly globalized world.

Gu Wenda Forest of Stone Steles - Retranslation & Rewriting of Tang Poetry 1993 - 2005. Hand-carved Stone. Dimensions of each stone stele: 110 cm (wide) x 190 cm (long) x 20 cm (thick)

Forest of Stone Steles - Retranslation & Rewriting of Tang Poetry is a large installation consisting of 50 hand-carved stone steles, every one of which weighs 1.3 tons. Gu needed twelve years and the collaboration if dozens of craftsman to complete this work.

Some cultural context: Stone steles have often been used as tombstones or markers of momentous events in Chinese history. And Xi’an, the city in which these stones were worked on, and the capital of four Chinese dynasties has an extensive “forest” of stone steles collected from every known period of Chinese history. Calligraphy was traditionally considered the highest form of visual art in China.

Each of the stones Forest of Stone Steles features a different Tang poem. Along with each of the original Tang poems, Gu gives a literal translation of the poem from Chinese to English, followed by a phonetic translation from English back into Chinese. Cultures themselves are imported and exported, exchanged and changed, assimilated and consumed. After all this, what remains of the original culture? In this work, Gu wished to give a sense of the un-translatability of a culture, despite what we might expect in this period of rapid globalization.

Gu Wenda, united nations: man and space 1999-2000 Human hair, glue, and twine 7600 cm x 800 cm

“united nations” is an ongoing series of installations which Wenda began in 1993. The works in each installation are “monuments” of hair. This particular installation recreates the flags of the 188 members of the United Nations. The hair used here was sourced from Gu’s stock of hair collected from over six million people on six continents. It was his largest installation in this series, produced and installed during the end of one century and the beginning of another.

Filling up multiple hallways, this work contains actual physical remnants of millions of people. Walking through these flags of hair is an invitation to consider the living presence of all the people and cultures and countries of the world, many of whom think of hair in vastly different ways. Juxtaposed in this way, the designs on the flags are strikingly similar. And the hair used for any flag may be from people from any and every country.

Gu Wenda Mythos of Lost Dynasties Series—Negative and Positive Characters 1984–85 Three hanging scrolls, ink on paper 9 ft. 4 5/8 in. × 68 1/2 in.

Each of the hanging scrolls in the above work contains the Chinese characters zheng (正) and fan (反). These characters can have a number of different meanings, depending on how they are arranged together: “front”, “back”, “orthodox”, “unorthodox”, “proper”, “improper”, “contrary”, and “correct”.

What is the correct interpretation of them then? Is there any proper or improper way to view them? On each of the three scrolls the characters are placed one above the other, but in each, one of the characters is also written backwards. There is no color, only black and white. There is a starkness and boldness in the characters on the center scroll, while the characters in the scrolls on the sides seem to be losing their character, with the black and white intermingling. There are also two swirling humanoid figures in deeper black seeming to stand in front of the characters in the flanking scrolls. Are the figures standing guard over the characters, or obscuring them?

Gu’s work always has socio-political connotations. But it remains open to interpretation, or eludes interpretation. Maybe the most successful political works are those which invite questions without necessarily providing answers.