Eighty-five years after WH Auden—at the time considered by many to be the best poet of his generation—wrote in his elegy for WB Yeats—who was thought of as the greatest poet writing in the English language, that “poetry makes nothing happen”—what purpose is there in finding ourselves and our words in the blank pages?

When genocides not only occur but are ignored, majorities actively vote against their own interests, and when truth can be dismissed as an “alternative fact”, where is a place of genuine belief we can write from? What does it mean to write when truth and meaning seem no longer foundational to our understanding of the world?

Rilke, like Yeats, his contemporary, still wrote with the certainty that poetry and poets were of the utmost importance to language, understanding, and humanity. To work our way towards an answer to the above questions, we can turn to a resonant concept from Rainer Maria Rilke. This concept is what Rilke called “Weltinnenraum", or World-Inner-Space.

Rilke’s "Weltinnenraum": The Inner World of Meaning

The World-Inner-Space is the place Rilke wrote from. And he thought of it as an actual place. Poetry itself to him was an extension of that place. Rilke's "Weltinnenraum" offers more than a poetic metaphor. It provides a framework for understanding how an enduring sense of meaning, essential for navigating the modern condition, can be developed from within human consciousness itself. The concept provided the architecture for all of his later poetry, including the two masterpieces he wrote not long before his final illness, the companion volumes Duino Elegies and Sonnets to Orpheus.

Rilke believed the world is not merely an external given, an object to be observed and categorized. Instead, it is something that asks to be translated into an interiority. This interiority, in Rilke’s understanding, is neither insulated nor merely reflective; it is permeable to and constitutive of the external. World-Inner-Space, then, enacts a radical collapsing of the conventional boundaries between inner and external phenomena.

"Weltinnenraum" presents a direct challenge to the traditional Western subject-object dichotomy. The visible world, in Rilke's conception, undergoes an alchemical process of internalization, transmuted through human consciousness into poetry and art. Phenomena do not merely pass by us, they enter us and add themselves into an innerspace of phenomena, where they acquire another reality.

Goethe wrote that “who wants to be a poet must go to the land of poetry.” For me, the Weltinnenraum has always been that land of poetry.

The Poet's Task: Inwarding and Praise

Rilke had always sought to compose what William H. Gass, in Reading Rilke: Reflections on the Problems of Translation, characterized as “poems that filled space as much as their subjects did.” He was a poet of the rose and the mirror. His ultimate artistic impulse was praise. As he urged himself and us, in the first Duino Elegy, to “begin again and again the never-attainable praising.”

This ambition of always beginning again the unattainable, Gass writes, led to a conviction

"that the world exists nowhere but within, and therefore the springtimes have need of us… and life and death run like hot and cold through the same tap; that love should give its beloved an unfastening and enabling freedom; that praise is the thing—they belong to no language, but to the realm of absolute image and pure idea, where a simple thought, or bare proportion can retain its elementary power…” (p. 79).

Perhaps we should consider the rose, a flower Rilke tended to all his life.

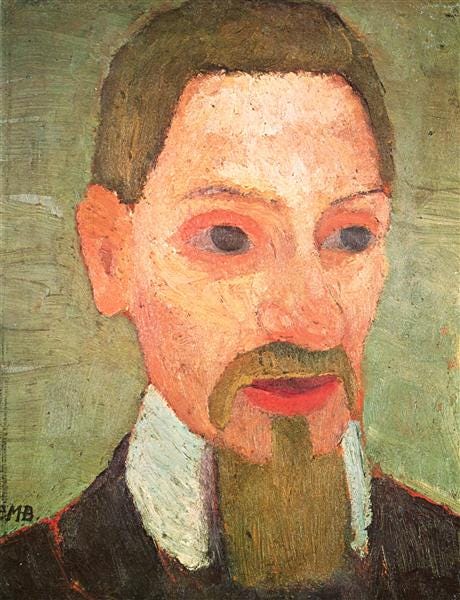

During one of the most important periods of his life, when he was in his mid-20’s and trying to find his style, Rilke lived at Worpswede, an artists’ colony near Bremen. Both a book of essays and poems about the colony and an exquisite diary covering his time there have been published. It was at Worpswede that he met his wife, the sculptor Clara Westhoff, and Paula Modersohn-Becker, for whom he would write one of his most moving poems, following her early death, “Requiem for a Friend.”

Portrait of Rainer Maria Rilke, 1906 - Paula Modersohn-Becker

One Sunday morning, in a romantic mood, Rilke brought his new friends a few flowers, and wrote about the gesture in his diary:

I invented a new form of caress: placing a rose gently on a closed eye until its coolness can no longer be felt; only the gentle petal will continue to rest on the eyelid like sleep just before dawn.

He might have left the rose on the closed eyelids of his friends, but he also carried it with him. It gave him the words for his epitaph: Rose, O pure contradiction, desire / to be no one's sleep beneath so many lids.

Wherever he went, trellises grew around him. When he finally found the style he had looked for so long, after passing through Paris and his time as an assistant to Rodin, and having those things pass through him, it was a gift of a bowl of rose that delivered his mature poetry to himself.

But now you know how to forget such things,

for now before you stands the bowl of roses,

unforgettable and wholly filled

with unattainable being and promise,

a gift Beyond anyone's giving, a presence

that might be our and our perfection.

-from "The Bowl of Roses", 1907About this poem, Gass wrote that “if the rose is not a poem, the poem is surely a rose.”

In one of the most gorgeous of the Sonnets to Orpheus, Rilke writes of the rose that “for us, you are the full, the numberless flower, / the inexhaustible countenance. // In your wealth you seem to be wearing gown upon gown / upon a body of nothing but light…”.

Rilke’s poet is not merely a recorder of events. The poet assumes a necessary task: to perform this interiorization, drawing the transient aspects of existence into the Weltinnenraum. There the things of the world are rescued from transience, and given an enduring presence, through the active will to praise. As he writes in the seventh sonnet to Orpheus: “Praising is what matters! He was summoned for that, / and came to us…like silence…./ For he is a herald who is with us always, / holding far into the doors of the dead / a ripe fruit worthy of praise.”

Rilke's metaphysics emerged not from abstraction but from seeing. Seeing the panther, the gazelle, the swan…a corps…a damaged sculpture…a forgotten portrait by a deceased friend. He refused to impose preconceived concepts upon the world he observed (as much, our postmodern mind might say, as he was able to), thus allowing him unimpeded access to the seen world. This intensely observed reality then became the material for the construction of a comprehensive inner space.

A central inquiry in German philosophy, for at least a century prior to his birth, was the hope to establish the relationship between mind and matter. How much of what was experienced was the world in itself, and how much was perception? In the moment of perception—when we allow such a state to exist within us—what we perceive then becomes existent within us.

Rilke’s entire artistic endeavor was predicated upon perception and reception. Perhaps this is why he so often fell in love with painters. Writing immediately after Nietzsche’s declaration of the death of god, and consciously distancing himself from Christianity, Rilke nonetheless approached every entity as an Ikon.

Or, at least, he strove to. Perhaps those fallow periods in his writing were precisely when he found himself unable to apprehend the world in this manner. It was a living iconography that allowed him an ever-expanding interiority and gave his poetry its astounding symbolic density.

For paid subscribers, the journey into Rilke's Weltinnenraum continues in the next installment. We'll delve into his pivotal "Wendeng"—his 'turning point'—and explore how his interior space liberates perception from impermanence, pointing the way to a 'secular transcendence' in the very heart of the world. Furthermore, we'll begin to draw unexpected parallels with Joseph Campbell's "mythogenic zone," forging a richer, more interwoven understanding of how we create meaning.

[Become a paid subscriber to receive Part 2 of this series in your inbox on July 22. Your support not only unlocks these deeper inquiries but also contributes to the ongoing exploration of poetry, meaning, and the creative life through exclusive content, including poetry prompts and what I'm reading now.]

Works Cited:

Gass, William H. Reading Rilke: Reflections on the Problems of Translation. Alfred A. Knopf, 1999.

Rilke, Rainer Maria. Ahead of All Parting: The Selected Poetry and Prose of Rainer Maria Rilke. Translated by Stephen Michell, Modern Library, 1997.

Rilke, Rainer Maria. Diaries of a Young Poet. Translated by Edward Snow and Michael Winkler, W.W. Norton, 1997.

Rilke, Rainer Maria. Letters on Cezanne. Fromm International, 1988.